Transformation, in the psychology of individuals, is a process of uncovering or discovering what is inside; of knowing oneself. Knowing oneself through discovery is different from creating oneself through invention.

Extracts from the book with the same title by Stanley M. Davis, recognised as a leader in organisation building and business transformations, addressing the toughest business challenges, published in BCC inhouse magazine July 1985 issue.

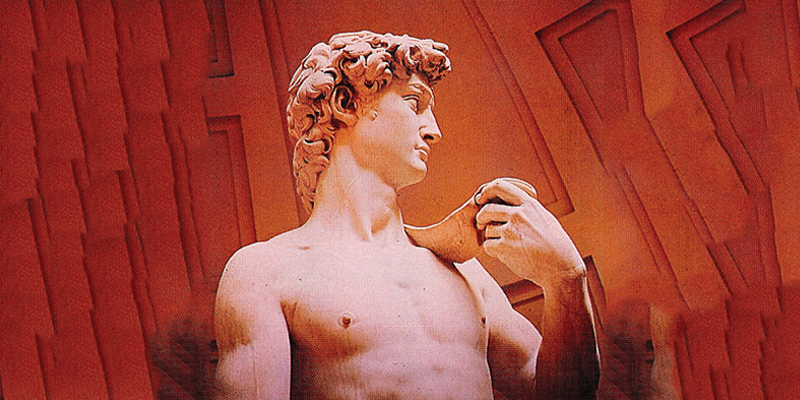

The lesser artist carves a figure out of stone. He believes the figure did not exist before he created it. Michelangelo began with the assumption that the figure was in the stone before he touched it. His statue of David in Florence is the best example of this approach. Only part of the figure is visible. His genius is that anyone looking at the statue knows that the rest is there within the encumbering stone.

Contexts are the unquestioned assumptions through which all experience is filtered. Context has no meaning - yet it provides, in Paul Tillich's* phrase, the "ground of being" from which content derives.

Context creates a reality, and the reality it creates is the content. Most managers manage the content, and only during a major strategic shift is the context brought into question. An operating budget or a two-year plan mainly provides content within a given and unquestioned context. The function of a ten¬-year plan is to provide the context. An organization's leadership will have implemented a long-range strategic plan when they manage the context, not the content.

Effectiveness and efficiency are the salt-and-pepper terms of management; we rarely see or use one without the other. The two are very distinct, however, and help clarify the difference between context and content. Effectiveness may be thought of as doing the right thing, and efficiency as doing that "thing" in the right way. The person who manages content can only improve the efficiency of the organization, and can never make it more effective. In this article, I will be focusing on how to make the context effective.

How are contexts created? Leaders should spend as much time posing questions as they do attempting to answer them. Perhaps they should spend even more time on framing them.

Context is created by the drawing of a boundary - the frame. What lies within the boundary becomes content. The reason that asking the right question is so important is that it determines the boundaries of the inquiry that is to follow. A question focuses attention, provides direction, and tells people where to look for the answer. Given that the boundary of inquiry is determined by the formulation of the question, what is inside that boundary becomes what we know that we don't know, and what we focus our attention on. What is outside the boundary of the question is, in effect, what we don't know that we don't know and therefore pay no attention to.

What, then, are the appropriate models specifically suited for corporations in the service economy? This is a question that transforms the context for developing models of management and organization.

The implementation phase of a strategic plan first must re-create this new context in each employee. Only after this is done will each employee be able to provide the appropriate methods (content) for carrying out his or her job as an element in fulfilling the strategic plan.

You have to know what you want to do before you can do it. The two elements of this statement - knowing what to do and knowing how to do it - are definitions of strategy and organization, respectively. Organization, here, refers to the culture, structure, systems, and people in the corporation.

Strategy is the plan for future survival. Organization is the current arrangement for day-to-day living. In principle the relation between the two is that a team, company, army, or nation should be organized in the manner that will best implement the strategy. A good strategy with poor organization is a thoroughbred without a rider, trainer, stable, or track. In principle, strategy precedes organization. Also in principle, the two are closely related; in practice, often they are not.

The proposition is that, by definition, organization always lags behind strategy. You have to know what it is you want to do before you can know how to do it. According to this logic, unless there are no changes in the environment or in the strategy, all organizations are created for businesses that either no longer exist or are in the process of going out of existence!

This is a very inert conception of organization. Organization does not have to be pulled along by the strategy. Organization can be used to push the strategy toward its realization. An organization's culture, structure, systems, and people can implement a strategic plan without the lag.

Is organizational lag necessary? Theoretically, there must be some; practically, there should be as little as possible. Remember, strategy is the allocation of future resources to anticipated demand. Strategy tells you what the business is going to look like; organization tells you how you are going to get it to be that way. Once the organization is "that" way, it has implemented the strategy; and when this has occurred, "that" is no longer the strategy. By definition there is no organization whose culture, structure, systems, and people are completely appropriate for its strategy. If all components of the organization were completely appropriate, the strategy would be realized; that is to say, it would be operational and no longer strategic. Successful strategy self-destructs. An objective, once accomplished, is no longer an objective. The realization of strategy is always futuristic. Because organization is the mechanism for implementing strategy, it is therefore the mechanism for realizing the future.

This is comparable to Michelangelo's approach to sculpture. The lesser artist carves a figure out of stone. He believes that the figure did not exist before he created it. He approaches the stone from the context that the figure is not there. Michelangelo began with the assumption that the figure was in the stone before he touched it. His job was to uncover the figure that was already there. His statues of the slaves, alongside his David in Florence, are the best example of this approach. Only part of the figures are visible; the rest are enslaved by the stone. His genius is that anyone looking at the statues knows that the rest of each body is there within the encumbering rock.

The effective organization, particularly its leadership, understands that it has already succeeded ("This is it"). The only problem is that not everybody in the organization knows this. If we assume, for example, that the new culture is out there to be gotten, then we don't have it, and in fact we never will. If we start from the context, "The way we behave is inappropriate; instead we must learn how to behave like ... ," then the message we are putting out is that we are not implementing the strategy.

If, on the other hand, we start from the context, "The way we behave is appropriate to the strategy," then the membership in the organization will know that their goals are being accomplished each moment. Each meeting, each decision, each activity is confirmation that the new culture "is". It already exists.

Those who lead an organization from this context are powerful because they already have what they want. By contrast, executives who lead from an orientation that what they want for the organization lies "out there" can be as powerful only in the never-realized future. That is to say, they are less powerful.

The term strategy as used in this context means a plan for the allocation of future resources to anticipated demand, and organization is a way of integrating existing resources to current demand. This corresponds, in many senses, to the two periods of formulating and implementing a long-range strategic plan.

We have seen from the classic paradigm that organization lags behind strategy, and that it is impossible to have the desired organization with a remedial, catch-up approach. To reiterate - by the time you get there, "there" isn't there anymore. "Getting there" - realizing a strategy - requires using a new paradigm, one that has a different conception of time. Put differently, by the time the desire is realized, it is no longer desired because it is no longer appropriate or needed.

How can this be avoided? How can an organization implement its strategic plan with actions that are appropriate to the presentfuture rather than with ones that are catching up with the past-present? The past, present, and future have to do, of course, with our traditional concept of time. A key element in implementing strategy involves a very different sense of time that has to do with managing from the new context.

The sense of time that executives employ with the classic model is to use the present organization as the vehicle for getting to the future, to the objective. At first glance this is logical. "What other organization can we use? It's the only one we've got." In the context of the classic model, that is true. In the new context, leaders operate from a different tense - from a different place in time. Implementing a strategic plan in the new context will require operating with a different concept of time.

The only way that an organization's leaders can get there (the objectives of the strategy) from here (the current organization) is to lead from a place in time that assumes you are already there, and that is determined even though it hasn't happened yet. This sounds bizarre or obscure only at first reading.

To explain this different sense of time requires a brief entry into the world of phenomenology and of semantics. Here, I will be drawing on the work of George Herbert Mead, Gordon Allport, B. F. Skinner, A. Schutz, and Karl Weick**. They hold that "an action can become an object of attention only after it has occurred. While it is occurring, it cannot be noticed." If everything is retrospective, then how are we to account for the fact that people and organizations plan and guide their actions according to their plans? Weick says that "even though a plan appears to be something oriented solely to the future, in fact it also has about it the quality of an act that has already been accomplished .... The actor visualizes the completed act, not the component actions that will bring about the completion." This last sentence may be restated to read, "The manager visualizes the completed strategy before visualizing the component actions that will bring about the completion.''

The implementation of a strategy has to be considered in the future-perfect tense. Using this time perspective, the present is the past of the future.

Two additional points flow from this:

"Visualizing the completed act" means, first, that the breakthrough quality of a plan lies in its totality. It cannot be appreciated and implemented fully - any more than it could have been conceived - if it is approached incrementally. The "component actions", the steps individuals will take in carrying out a plan, will be suboptimal unless each individual first apprehends the completed totality.

Being comfortable with contradictory formulations (thesis and antithesis) is the only path to resolution in a larger synthesis. Subcultures in an organization, for example, generally are held as contradictory formulations by the membership. Trying to blend subcultures will not lead to a synthesis, because it tries to eliminate or deny the contradictions. The prelude to synthesis, and the emergence of a unified culture that is appropriate for a new strategy, will only occur by allowing the paradox to be. Leaders have to take this approach consistently, even though to do so will be very confusing in the early stages.

Human beings discover their humanity; they don't invent it. Most of us are familiar with the maxim, "Necessity is the mother of invention." Necessity bespeaks need, survival, and scarcity. To premise a strategic plan or a corporation's culture on invention is to create within a framework of scarcity. If, however, necessity is the mother of invention, then abundance is the mother of discovery. A long-range strategic plan for a declining business has to be created in the framework of abundance. That framework is not the context of increased competition and declining profit margins.

Rather, it is the context that whatever is replacing the dominance of the past has an abundance that needs to be discovered and linked up with.

In the same sense, the culture of an organization cannot be invented -it can only be discovered. Inventing the culture would mean operating in a context of scarcity. It would be the presumption, "We don't have what we need, and we need to develop it." This is quite a powerless position to start from; it is also a costly one because it assumes that enormous resources will have to be expended to eliminate the scarcity.

I wish to return here, briefly, to basic philosophical abstractions. Transformation, in the psychology of individuals, is a process of uncovering or discovering what is inside; of knowing oneself. Knowing oneself through discovery is different from creating oneself through invention. Here, again, we are in the realm of the essence-versus-existence dilemma. Essence, or context, has a certain intangibility. It is not a thing or an event. It is a space in which things and events come into existence. The power of a strategic plan lies in the context it uncovers, in its essence-ness.

If we understand discovery as redefining the context, and invention as the outcome of a redefined context, then we come close to a marketing orientation for strategic planning. In the same way that content is a consequence of the context, products are a consequence of the marketing effort in a marketing-focused business.

Getting back to management, an analogy might help. Think of two airplanes, one subsonic and the other supersonic, travelling from point (1) to (2). The sound emitted from the subsonic plane reaches point (2) at the same time the plane does. The supersonic plane, however, reaches point (2) before its sound does.

Imagine arriving in a plane at (2) and then waiting for the arrival of your own sound. In this context, you are there before the fact. You have created a phenomenon, gotten ahead of it after it was created, and observed it catch up with you.

Education may be viewed as the acquisition of knowledge, whereas enlightenment is to be possessed of wisdom. Knowledge is accumulated in discrete bits; wisdom is not divisible and cumulative. Because knowledge is incremental, it is also measurable; wisdom is not. What would happen to our institutions of higher learning if the focus of the instructors were on wisdom through enlightenment rather than on knowledge through education? What would happen in business corporations if strategic planning or any other organizational task were approached from the perspective of an enlightened shift in context rather than as an educated change in content?

In this new context, formulation of a strategy is not the first step in its implementation; rather, it is the first piece of evidence that it already has been implemented. Each succeeding step is not then built on the ones preceding. One does not, for example, build an organization's new culture by spreading, replicating, and extending desirable behaviour. That desired behaviour can be re-created. Each re-creation is evidence of the presence of the new culture, just as each undesirable action is evidence of the continuation of the old conflicting subcultures. More of the new and less of the old will have represented a shift in content. In each individual, at some point in time, that leap will have occurred and the organization's context and his or her behaviour in it will be altered forever.

Stanley H Davis is the Founding Principal of US Standish Executive Search, an executive recruiting and organisation advisory firm positioning businesses for growth, change or succession. As an advisor and a corporate leader, he has worked closely with business owners, CEOs and their staffs to initiate and execute aggressive talent and organisation strategies to significantly improve business results. He is also co-author of books, such as Introduction to Total Quality: Quality, Productivity, Competitiveness (1994) and Quality Management for Organizational Excellence: Introduction to Total Quality (2012).

Michelangelo, in full Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, (born 6 March 1475 in Florence, Italy, was an Italian Renaissance sculptor, painter, architect, and poet who exerted an unparalleled influence on the development of Western art. He was considered the greatest living artist in his lifetime, and ever since then he has been held to be one of the greatest artists of all time. A number of his works in painting, sculpture and architecture are among the most famous in existence. The frescoes (mural paintings) on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican are the best known of his works.

*Paul Tillich, (1886 - 1965), was a German-born U.S. theologian and philosopher whose discussions of God and faith illuminated and bound together the realms of traditional Christianity and modern culture. He believed that capitalism and its institutions were inherently unjust and had a destructive effect on the community. Tillich relied heavily on the dialectical approach in his attempts to integrate psychology, sociology, history, economics and philosophy into his theology. He also stressed the positive aspect of technology, saying that it can be used to achieve social justice.

**George Herbert Mead (1863 - 1961) is a major figure in the history of American philosophy, who developed the concept of self, which explains that one's identity emerges out of external social interactions and internal feelings of oneself. According to Mead, the self resides in the individual's ability to take account of himself or herself as a social being. The organised community or social group which gives to the individual his or her unity of self may be called “the generalized other.”

**Gordon Allport (1897 - 1967) was a pioneering American psychologist often referred to as one of the founders of personality psychology. He stressed the importance of individual differences and situational variables. His entire approach to psychology, and more specifically to personality, was born of his strong devotion to social ethics. He was a profoundly spiritual man, who challenged the negative aspects of religious dogma and championed the positive aspects of having a spiritual direction in one’s life. His approach emphasized the value and uniqueness of each person.

**B. F. Skinner, in full Burrhus Frederic Skinner, (1904 – 1990) was an American psychologist and an influential exponent of behaviourism, which views human behaviour in terms of responses to environmental stimuli and favours the controlled, scientific study of responses as the most direct means of explaining human nature. Skinner saw human action as dependent on consequences of previous actions, a theory he would articulate as the principle of reinforcement: If the consequences to an action are bad, there is a high chance the action will not be repeated; if the consequences are good, the probability of the action being repeated becomes stronger.

**Alfred Schutz, (1899 - 1959), was an Austrian-born U.S. sociologist and philosopher who developed a social science based on phenomenology. Literally, phenomenology is the study of “phenomena” or occurrences: appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience. It is a way of thinking about ourselves. Instead of asking about what we really are, it focuses on phenomena. These are experiences that we get from the senses - what we see, taste, smell, touch, hear, and feel. Anything that is or can be experienced or felt, especially something that is noticed because it is unusual or new.

**Karl Weick (b. 1936) is a leading international scholar, writing on aspects of organisational behaviour and has become world renowned for his insights into why people in organisations act the way they do. His major contributions in an organisational context are concepts such as loose coupling a term intended to capture the necessary degree of flex between an organisation's internal abstraction of reality, sensemaking where people try to make sense of organisations, and organisations themselves try to make sense of their environment; collective mindfulness when we realise our current expectations, continuously improve those expectations based on new experiences, and implement those expectations to improve the current situation into a better one; organisational information theory that addresses how organisations reduce equivocality allowing the possibility of several different meanings, or uncertainty through a process of information collection, management and use.